Ever since I was a kid, Currimao in Ilocos Norte has always had a special place in my heart. It has decent packets of beaches very close to where I live, making it an easy weekend getaway. Pangil, one of its barangays, offers what I would describe as the site of the most romantic sunset one can witness in the north thanks to its dramatic rocky landscape. It’s very easy to fall in love with it. Aside from this, however, I did not know anything else about this small, sleepy town by the sea.

Well, until recently[1].

A Reminder of the Tobacco Trade

During the Spanish period, Currimao, which was still a part of Paoay, was a commercial port that played an important role in the tobacco trade. The northern Philippines was then known to have focused on this cash crop, supplying not only local demands but even those from overseas. The town has an 1869-built almacen, popularly known today as the tabacalera, which was used by the Compania General de los Tabacos de Filipinas. There are two other extant tabacaleras in the province, one in Laoag[2] and another in Dingras. But, what makes Currimao’s tabacalera special is that it was at the forefront of the trade given its strategic location and access to the open waters.

Inside the tabacalera ruins

The massive structure follows a simple rectangular floor plan, with all sides supported by identical buttresses reminiscent of earthquake baroque churches. It also has gabled ends and what appears to be a portico on the main portal. Vestiges of an old perimeter wall made of the same materials used in constructing the almacen – rocks, coral stones and ladrillos – can be found around it as well.

Exterior of the tabacalera with its buttresses, and the mess around it.

Given its already fragile condition, what is more disturbing, however, is the obvious neglect of the site by the locals. Currently, it is used as a heavy equipment and motor pool, as well as a dump site for gravel and aggregates for construction works. This is alarming because its state of disrepair might jeopardize the ongoing process to designate the site yet another National Cultural Treasure – a procedure to be completed, hopefully, by next year[3].

The almacen sits just a few meters away from an old yet still functioning pantalan or wharf that is made of coral stones[4]. This, however, was cemented with concrete a few years ago giving a very modern appearance to it nowadays. Also, close to the almacen, to its left, is another ruins of what might have been the aduana or the customs office[5]. Presently, the remains of this brick edifice is within a private property and no one really knows what will happen to it nor can anyone guarantee its preservation. Furthermore, a few meters again from the ruins is an agua del pozo[6] or a water well. Aside from it still being used, what is more impressive about this simple structure is that it is dated: 12 de Diciembre de 1878 ano.

The Spanish period well with the date of its construction

Man-made Fortifications

Across the archipelago, there are hundreds of watchtowers and fortresses built by the Spaniards in their attempt to fortify their empire in the Pacific[7]. Ilocos Norte alone has six, and neighboring Ilocos Sur has five. The existence of a twin watchtowers or garitas only reinforces the historical – and commercial – importance of Currimao as a port. In the Philippines, I am only aware of one other town where a twin watchtowers also exist: Romblon, Romblon[8]. Furthermore, the twin watchtowers of Romblon and Currimao have another striking resemblance: their fortifications can be found at either ends of their poblacion harbour. Their only difference is that, for Romblon, the watchtowers were meant to guard over the pueblo with a church, while Currimao’s were meant to watch over a coastal settlement with a tabacalera.

The eastern watchtower

The more obvious of the two watchtowers in Currimao is partly damaged as a segment of its wall has already collapsed. This one is noticeable at any point along the seawall as it prominently stands at the eastern end of the harbour, without any obstruction surrounding it[9]. The other watchtower, which is still complete, is currently heavily vegetated. Several concrete structures have also already been built around it, thus compromising its visual integrity[10]. Both of these watchtowers, which stand approximately seven meters high, are thought to have been built in the mid 1800s or even much earlier.

The western watchtower

Despite having been declared as National Cultural Treasures in 2015 under the serial inscription “Watchtowers of Ilocos Norte”[11], there is still the urgent need to conserve and restore the structures that are clearly under threats caused by human negligence and natural disasters.

The Coral Rocks as Natural Barriers

Currimao also boasts a unique landscape and seascape. It is home to a very long coral rock formation along its coast. The entire length of this geological curiosity spans nearly three kilometers, and the best exponents of it are found in Barangay Pangil.

The sharp coral cocks make it impossible for boats and ships to get any closer than 100 metres to shore.

What many might not realize, however, is that these sharp ancient rocks form a durable wall, which creates a natural fortification for the community. During the time when the tobacco trade was at its peak (as a component of the Galleon trade), threats from invading Moros and Chinese pirates were very common in the area. This is also the reason why the watchtowers have come to be known locally as the Moro watchtowers. But, given its rocky shores, boats, let alone ships, cannot dock just anywhere; the rocks and waves make that impossible. Hence, anyone who wished to make a landing would have to go to the only area devoid of coral rocks – the poblacion harbour.

The coral rocks can rise as high as four meters above the water line.

Until now, it is only this particular area where fishermen can safely dock their fishing boats and rafts (with the exception, of course, of the more sandy shores of Victoria and Gaang that are already far away from the poblacion). The Spaniards erected the watchtowers precisely where the natural fortifications ceased.

Fortified Commercial Complex?

A good fortification utilizes elements in its surroundings to its advantage. The coral rocks and the watchtowers complemented each other in as far as guarding Currimao and its commercial activities were concerned. This outstanding system of natural barriers and man-made fortifications made the poblacion of Currimao a highly defensive coastal settlement by Philippine standards at that time. With the presence of the ruins of an almacen and an aduana, a functioning agua del pozo and pantalan, as well as two garitas, together with its imposing long coral rock formations, it is only fitting to reassess, rethink, and reintroduce the poblacion of Currimao – yes, the small, sleepy town – as an intact, fortified, Spanish-period commercial complex that might be hard to match elsewhere in the country.

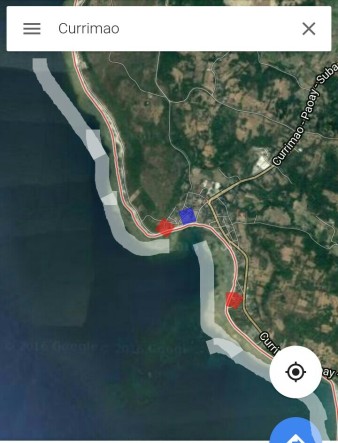

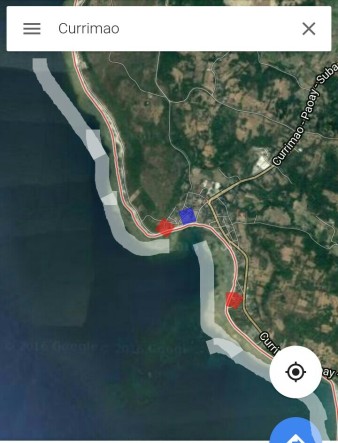

Legend: Blue – location of the almacen, aduana, pozo del agua, and pantalan; red – the two garitas declared as National Cultural Treasures; grey – the coastal areas with coral rocks.

___________________________

[1] Performed cultural mapping and documentation in town on March 14, 2016 for www.philippineheritagemap.org

[2] Presently housing the Ilocos Norte Museum

[3]“Pending cultural properties for consideration for declaration as Important Cultural Properties or National Cultural Treasures by the National Museum in 2016” http://www.ivanhenares.com/2015/12/national-cultural-treasure-2015.html

[4] http://philippineheritagemap.org/reports/14231c4b-5ae5-46ac-a911-77d384e4bf1f

[5] http://philippineheritagemap.org/reports/54b3d96f-5c09-4cc6-b4af-f5cf8aed0d78

[6] http://philippineheritagemap.org/reports/85df66cc-a2f5-4a5a-a704-506c873f4984

[7] Javellana, R (1997). Fortress of empire: Spanish colonial fortification of the Philippines, 1565 to 1898. Manila: Bookmark. Also look at http://simbahan.net/2009/08/27/fortress-of-empire-rene-javellana-sj/

[8] Fort San Andres was a component of the now widthrawn “Spanish Fortifications of the Philippines” nomination for UNESCO World Heritage Site listing. It is also a declared National Cultural Treasure. Its twin Fort Santiago is already in ruins. Also look at http://pamana.ph/fort-san-andres/

[9] http://philippineheritagemap.org/reports/ede424b7-984b-4e21-ac9e-e83c3d45241a

[10] http://philippineheritagemap.org/reports/df3a9836-4f09-441f-9745-a0fa6049ef42

[11] http://ncca.gov.ph/national-museum-bares-2015-list-of-cultural-treasures-properties/